Brexit: London risks losing its role as banker to the world

29 de janeiro de 2020

Genetic Testing for Kids: Is It a Good Idea?

5 de fevereiro de 2020When, in 1960, still a student, I got a traveling fellowship to study housing in North America. We traveled the country. We saw public housing high-rise buildings in all major cities: New York, Philadelphia. Those who have no choice lived there. And then we traveled from suburb to suburb, and I came back thinking, we’ve got to reinvent the apartment building. There has to be another way of doing this. We can’t sustain suburbs, so let’s design a building which gives the qualities of a house to each unit.

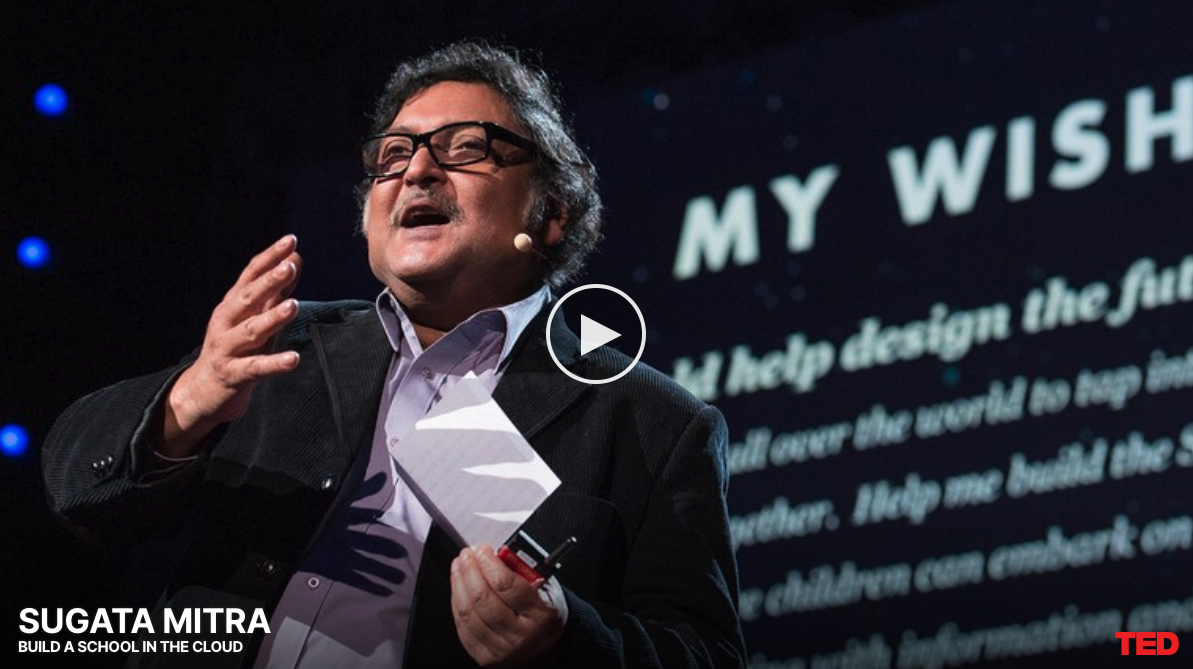

What is going to be the future of learning?

I do have a plan, but in order for me to tell you what that plan is, I need to tell you a little story, which kind of sets the stage.

I tried to look at where did the kind of learning we do in schools, where did it come from? And you can look far back into the past, but if you look at present-day schooling the way it is, it’s quite easy to figure out where it came from. It came from about 300 years ago, and it came from the last and the biggest of the empires on this planet. [“The British Empire”] Imagine trying to run the show, trying to run the entire planet, without computers, without telephones, with data handwritten on pieces of paper, and traveling by ships. But the Victorians actually did it. What they did was amazing. They created a global computer made up of people. It’s still with us today. It’s called the bureaucratic administrative machine. In order to have that machine running, you need lots and lots of people. They made another machine to produce those people: the school. The schools would produce the people who would then become parts of the bureaucratic administrative machine. They must be identical to each other. They must know three things: They must have good handwriting, because the data is handwritten; they must be able to read; and they must be able to do multiplication, division, addition and subtraction in their head. They must be so identical that you could pick one up from New Zealand and ship them to Canada and he would be instantly functional. The Victorians were great engineers.They engineered a system that was so robust that it’s still with us today, continuously producing identical people for a machine that no longer exists. The empire is gone, so what are we doing with that design that produces these identical people, and what are we going to do next if we ever are going to do anything else with it?

[“Schools as we know them are obsolete”]

So that’s a pretty strong comment there. I said schools as we know them now, they’re obsolete. I’m not saying they’re broken. It’s quite fashionable to say that the education system’s broken. It’s not broken. It’s wonderfully constructed. It’s just that we don’t need it anymore. It’s outdated. What are the kind of jobs that we have today? Well, the clerks are the computers. They’re there in thousands in every office. And you have people who guide those computers to do their clerical jobs. Those people don’t need to be able to write beautifully by hand. They don’t need to be able to multiply numbers in their heads. They do need to be able to read. In fact, they need to be able to read discerningly.

Well, that’s today, but we don’t even know what the jobs of the future are going to look like. We know that people will work from wherever they want, whenever they want, in whatever way they want. How is present-day schooling going to prepare them for that world?

Well, I bumped into this whole thing completely by accident. I used to teach people how to write computer programs in New Delhi, 14 years ago. And right next to where I used to work, there was a slum. And I used to think, how on Earth are those kids ever going to learn to write computer programs? Or should they not? At the same time, we also had lots of parents, rich people, who had computers, and who used to tell me, “You know, my son, I think he’s gifted, because he does wonderful things with computers. And my daughter — oh, surely she is extra-intelligent.” And so on. So I suddenly figured that, how come all the rich people are having these extraordinarily gifted children? (Laughter) What did the poor do wrong? I made a hole in the boundary wall of the slum next to my office, and stuck a computer inside it just to see what would happen if I gave a computer to children who never would have one, didn’t know any English, didn’t know what the Internet was.

The children came running in. It was three feet off the ground, and they said, “What is this?”

And I said, “Yeah, it’s, I don’t know.” (Laughter)

They said, “Why have you put it there?”

I said, “Just like that.”

And they said, “Can we touch it?”I said, “If you wish to.”

And I went away. About eight hours later, we found them browsing and teaching each other how to browse. So I said, “Well that’s impossible, because — How is it possible? They don’t know anything.”

My colleagues said, “No, it’s a simple solution. One of your students must have been passing by, showed them how to use the mouse.”

So I said, “Yeah, that’s possible.”

So I repeated the experiment. I went 300 miles out of Delhi into a really remote village where the chances of a passing software development engineer was very little. (Laughter) I repeated the experiment there. There was no place to stay, so I stuck my computer in, I went away, came back after a couple of months, found kids playing games on it.

When they saw me, they said, “We want a faster processor and a better mouse.”

So I said, “How on Earth do you know all this?”

And they said something very interesting to me. In an irritated voice, they said, “You’ve given us a machine that works only in English, so we had to teach ourselves English in order to use it.” That’s the first time, as a teacher, that I had heard the word “teach ourselves” said so casually.

Here’s a short glimpse from those years. That’s the first day at the Hole in the Wall. On your right is an eight-year-old. To his left is his student. She’s six. And he’s teaching her how to browse. Then onto other parts of the country, I repeated this over and over again, getting exactly the same results that we were. [“Hole in the wall film – 1999”] An eight-year-old telling his elder sister what to do. And finally a girl explaining in Marathi what it is, and said, “There’s a processor inside.”

So I started publishing. I published everywhere. I wrote down and measured everything, and I said, in nine months, a group of children left alone with a computer in any language will reach the same standard as an office secretary in the West. I’d seen it happen over and over and over again.

But I was curious to know, what else would they do if they could do this much? I started experimenting with other subjects, among them, for example, pronunciation. There’s one community of children in southern India whose English pronunciation is really bad, and they needed good pronunciation because that would improve their jobs. I gave them a speech-to-text engine in a computer, and I said, “Keep talking into it until it types what you say.” (Laughter) They did that, and watch a little bit of this.

Computer: Nice to meet you. Child: Nice to meet you.

Sugata Mitra: The reason I ended with the face of this young lady over there is because I suspect many of you know her. She has now joined a call center in Hyderabad and may have tortured you about your credit card bills in a very clear English accent.

So then people said, well, how far will it go? Where does it stop? I decided I would destroy my own argument by creating an absurd proposition. I made a hypothesis, a ridiculous hypothesis. Tamil is a south Indian language, and I said, can Tamil-speaking children in a south Indian village learn the biotechnology of DNA replication in English from a street side computer? And I said, I’ll measure them. They’ll get a zero. I’ll spend a couple of months, I’ll leave it for a couple of months, I’ll go back, they’ll get another zero. I’ll go back to the lab and say, we need teachers. I found a village. It was called Kallikuppam in southern India. I put in Hole in the Wall computers there, downloaded all kinds of stuff from the Internet about DNA replication, most of which I didn’t understand.

The children came rushing, said, “What’s all this?”

So I said, “It’s very topical, very important. But it’s all in English.”

So they said, “How can we understand such big English words and diagrams and chemistry?”

So by now, I had developed a new pedagogical method, so I applied that. I said, “I haven’t the foggiest idea.” (Laughter) “And anyway, I am going away.” (Laughter)

So I left them for a couple of months. They’d got a zero. I gave them a test. I came back after two months and the children trooped in and said, “We’ve understood nothing.”

So I said, “Well, what did I expect?” So I said, “Okay, but how long did it take you before you decided that you can’t understand anything?”

So they said, “We haven’t given up. We look at it every single day.”

So I said, “What? You don’t understand these screens and you keep staring at it for two months? What for?”

So a little girl who you see just now, she raised her hand, and she says to me in broken Tamil and English, she said, “Well, apart from the fact that improper replication of the DNA molecule causes disease, we haven’t understood anything else.”

So I tested them. I got an educational impossibility, zero to 30 percent in two months in the tropical heat with a computer under the tree in a language they didn’t know doing something that’s a decade ahead of their time. Absurd. But I had to follow the Victorian norm. Thirty percent is a fail. How do I get them to pass? I have to get them 20 more marks. I couldn’t find a teacher. What I did find was a friend that they had, a 22-year-old girl who was an accountant and she played with them all the time.

So I asked this girl, “Can you help them?”

So she says, “Absolutely not. I didn’t have science in school. I have no idea what they’re doing under that tree all day long. I can’t help you.”

I said, “I’ll tell you what. Use the method of the grandmother.”

So she says, “What’s that?”

I said, “Stand behind them. Whenever they do anything, you just say, ‘Well, wow, I mean, how did you do that? What’s the next page? Gosh, when I was your age, I could have never done that.’ You know what grannies do.”

So she did that for two more months. The scores jumped to 50 percent. Kallikuppam had caught up with my control school in New Delhi, a rich private school with a trained biotechnology teacher. When I saw that graph I knew there is a way to level the playing field.

Here’s Kallikuppam.

(Children speaking) Neurons …communication.

I got the camera angle wrong. That one is just amateur stuff, but what she was saying, as you could make out, was about neurons, with her hands were like that, and she was saying neurons communicate. At 12.

So what are jobs going to be like? Well, we know what they’re like today. What’s learning going to be like? We know what it’s like today, children pouring over with their mobile phones on the one hand and then reluctantly going to school to pick up their books with their other hand.

What will it be tomorrow? Could it be that we don’t need to go to school at all? Could it be that, at the point in time when you need to know something, you can find out in two minutes? Could it be — a devastating question, a question that was framed for me by Nicholas Negroponte — could it be that we are heading towards or maybe in a future where knowing is obsolete? But that’s terrible. We are homo sapiens. Knowing, that’s what distinguishes us from the apes. But look at it this way. It took nature 100 million years to make the ape stand up and become Homo sapiens. It took us only 10,000 to make knowing obsolete. What an achievement that is. But we have to integrate that into our own future.

Encouragement seems to be the key. If you look at Kuppam, if you look at all of the experiments that I did, it was simply saying, “Wow,” saluting learning.

There is evidence from neuroscience. The reptilian part of our brain, which sits in the center of our brain, when it’s threatened, it shuts down everything else, it shuts down the prefrontal cortex, the parts which learn, it shuts all of that down. Punishment and examinations are seen as threats. We take our children, we make them shut their brains down, and then we say, “Perform.” Why did they create a system like that? Because it was needed. There was an age in the Age of Empires when you needed those people who can survive under threat. When you’re standing in a trench all alone, if you could have survived, you’re okay, you’ve passed. If you didn’t, you failed. But the Age of Empires is gone. What happens to creativity in our age? We need to shift that balance back from threat to pleasure.

I came back to England looking for British grandmothers. I put out notices in papers saying, if you are a British grandmother, if you have broadband and a web camera, can you give me one hour of your time per week for free? I got 200 in the first two weeks. I know more British grandmothers than anyone in the universe. (Laughter) They’re called the Granny Cloud. The Granny Cloud sits on the Internet. If there’s a child in trouble, we beam a Gran. She goes on over Skype and she sorts things out. I’ve seen them do it from a village called Diggles in northwestern England, deep inside a village in Tamil Nadu, India, 6,000 miles away. She does it with only one age-old gesture. “Shhh.” Okay?

Watch this.

Grandmother: You can’t catch me. You say it. You can’t catch me.

Children: You can’t catch me.

Grandmother: I’m the Gingerbread Man. Children: I’m the Gingerbread Man.

Grandmother: Well done! Very good.

SM: So what’s happening here? I think what we need to look at is we need to look at learning as the product of educational self-organization. If you allow the educational process to self-organize, then learning emerges. It’s not about making learning happen. It’s about letting it happen. The teacher sets the process in motion and then she stands back in awe and watches as learning happens. I think that’s what all this is pointing at.

But how will we know? How will we come to know? Well, I intend to build these Self-Organized Learning Environments. They are basically broadband, collaboration and encouragement put together. I’ve tried this in many, many schools.

It’s been tried all over the world, and teachers sort of stand back and say, “It just happens by itself?”

And I said, “Yeah, it happens by itself.””How did you know that?”

I said, “You won’t believe the children who told me and where they’re from.”

Here’s a SOLE in action.

(Children talking)

This one is in England. He maintains law and order, because remember, there’s no teacher around.

Girl: The total number of electrons is not equal to the total number of protons — SM: Australia Girl: — giving it a net positive or negative electrical charge. The net charge on an ion is equal to the number of protons in the ion minus the number of electrons.

SM: A decade ahead of her time.

So SOLEs, I think we need a curriculum of big questions. You already heard about that. You know what that means. There was a time when Stone Age men and women used to sit and look up at the sky and say, “What are those twinkling lights?” They built the first curriculum, but we’ve lost sight of those wondrous questions. We’ve brought it down to the tangent of an angle. But that’s not sexy enough. The way you would put it to a nine-year-old is to say, “If a meteorite was coming to hit the Earth, how would you figure out if it was going to or not?” And if he says, “Well, what? how?” you say, “There’s a magic word. It’s called the tangent of an angle,” and leave him alone. He’ll figure it out.

So here are a couple of images from SOLEs. I’ve tried incredible, incredible questions — “When did the world begin? How will it end?” — to nine-year-olds. This one is about what happens to the air we breathe. This is done by children without the help of any teacher. The teacher only raises the question, and then stands back and admires the answer.

So what’s my wish? My wish is that we design the future of learning. We don’t want to be spare parts for a great human computer, do we? So we need to design a future for learning. And I’ve got to — hang on, I’ve got to get this wording exactly right, because, you know, it’s very important. My wish is to help design a future of learning by supporting children all over the world to tap into their wonder and their ability to work together. Help me build this school. It will be called the School in the Cloud. It will be a school where children go on these intellectual adventures driven by the big questions which their mediators put in. The way I want to do this is to build a facility where I can study this. It’s a facility which is practically unmanned. There’s only one granny who manages health and safety. The rest of it’s from the cloud. The lights are turned on and off by the cloud, etc., etc., everything’s done from the cloud.

But I want you for another purpose. You can do Self-Organized Learning Environments at home, in the school, outside of school, in clubs. It’s very easy to do. There’s a great document produced by TED which tells you how to do it. If you would please, please do it across all five continents and send me the data, then I’ll put it all together, move it into the School of Clouds, and create the future of learning. That’s my wish.

And just one last thing. I’ll take you to the top of the Himalayas. At 12,000 feet, where the air is thin, I once built two Hole in the Wall computers, and the children flocked there. And there was this little girl who was following me around.

And I said to her, “You know, I want to give a computer to everybody, every child. I don’t know, what should I do?” And I was trying to take a picture of her quietly.

She suddenly raised her hand like this, and said to me, “Get on with it.”

I think it was good advice. I’ll follow her advice. I’ll stop talking. Thank you. Thank you very much.(Applause) Thank you. Thank you. (Applause) Thank you very much. Wow. (Applause)

Texto em Português:

Qual será o futuro do aprendizado?

Eu tenho um plano, mas para que eu possa contar que plano é esse, preciso contar uma pequena história pra vocês, que vai preparar o terreno.

Eu tentei analisar de onde… o tipo de aprendizado que temos nas escolas, de onde ele veio? E você pode olhar para o passado, mas se analisarmos a escolarização como ela é hoje, é bem fácil descobrir de onde ela veio. Veio cerca de 300 anos atrás, e veio do último e maior dos impérios deste planeta. [“O Império Britânico”] Imagine tentar comandar o show, tentar comandar o planeta inteiro, sem computadores, sem telefones, com informações escritas à mão em papel, e viajando em navios. Mas os vitorianos realmente o fizeram. O que eles fizeram foi incrível. Eles criaram um computador global feito de pessoas. Ele ainda está conosco hoje. É a chamada máquina administrativa burocrática. Para que essa máquina siga funcionando, você precisa de muitas e muitas pessoas. Eles fizeram outra máquina para produzir essas pessoas: a escola. As escolas produziriam as pessoas que depois se tornariam parte da máquina administrativa burocrática. Elas devem ser idênticas umas às outras. E devem saber três coisas: devem ter uma boa caligrafia, pois a informação é escrita à mão; devem saber ler; e devem ser capazes de fazer multiplicação, divisão, adição e subtração de cabeça. Devem ser idênticas ao ponto de você poder selecionar uma da Nova Zelândia e enviá-la ao Canadá, onde ela seria imediatamente funcional. Os vitorianos eram grandes engenheiros. Eles criaram um sistema tão robusto que ainda está conosco hoje, continuamente produzindo pessoas idênticas para uma máquina que não existe mais. O império se foi, então o que estamos fazendo com esse modelo que produz essas pessoas idênticas, e o que vamos fazer em seguida, se algum dia fizermos algo diferente com isso?

[“As escolas como as conhecemos estão obsoletas”]

Eis um comentário bem forte. Eu disse que as escolas como as conhecemos estão obsoletas. Não estou dizendo que estão falidas. Está muito na moda dizer que o sistema educacional está falido. Não está falido. Ele é incrivelmente estruturado. Só que não precisamos mais dele. Está desatualizado. Quais são os tipos de trabalho que temos hoje? Bom, os escrivães são os computadores. Em cada escritório há centenas deles. E temos pessoas que operam esses computadores para realizar trabalhos burocráticos. Essas pessoas não precisam ter uma caligrafia maravilhosa. Elas não precisam saber multiplicar números de cabeça. Elas precisam ser capazes de ler. Na verdade, elas precisam saber ler com discernimento.

Bom, isso é hoje, mas nem sabemos como serão os trabalhos do futuro. Sabemos que as pessoas vão trabalhar de onde quiserem, quando quiserem, da forma que quiserem. Como a educação dos dias atuais vai prepará-las para esse mundo?

Bom, eu me deparei com tudo isso por acaso. Eu ensinava as pessoas a escrever programas de computador em Nova Delhi, 14 anos atrás, e bem ao lado de onde eu trabalhava, havia uma favela. E eu ficava pensando: “Como todas essas crianças aprenderão a escrever programas de computador?” Ou não deveriam aprender? Ao mesmo tempo, tínhamos muitos pais, pessoas ricas, que tinham computadores, que vinham me dizer: “Sabe, meu filho, acho que ele tem um dom, porque ele faz coisas incríveis com computadores. E minha filha… ah, ela é inteligente demais”. Então, eu percebi: como é que todas essas pessoas ricas estão tendo essas crianças superdotadas?(Risos) O que havia de errado com os pobres? Eu fiz um buraco no muro que separava meu escritório da favela, e coloquei um computador lá só pra ver o que aconteceria se eu desse um computador para crianças que nunca tiveram um, que não soubessem inglês, não soubessem o que era Internet.

Ficava a um metro do chão, e elas vieram e disseram: “O que é isso?”

E eu disse: “Bom… eu não sei”.

E elas: “Por que você colocou isso aí?”

E eu disse: “Assim mesmo”.

E elas: “Podemos tocar?” E eu: “Se vocês quiserem, sim”.

E me afastei. Umas oito horas depois, vimos que estavam navegando e ensinando os outros como navegar. E eu disse: “Isso é impossível, porque… Como é possível? Eles não sabem nada”.

Meus colegas disseram: “Não, a solução é simples. Um dos seus alunos devia estar passando e mostrou a eles como usar o mouse”.

E eu disse: “É, pode ser isso”.

Então, repeti o experimento: fui a uma vila bem remota, a uns 500 km de Delhi, onde a chance de um engenheiro de software passar… (Risos) era muito pequena. Lá, repeti o experimento. Não havia lugar para ficar, deixei o computador, fui embora, voltei uns dois meses depois e encontrei crianças rodando jogos nele.

Quando me viram, disseram: “Queremos um processador e um mouse melhores”.

Então, eu disse: “Como é que vocês sabem tudo isso?”

E elas me disseram algo muito interessante. Em tom irritado, disseram: “Você nos deu uma máquina que só funciona em inglês. Tivemos que aprender inglês sozinhos para poder usá-la. (Risos) Foi a primeira vez, como professor, que eu ouvi a frase “aprender sozinhos” dita tão naturalmente.

Eis algumas imagens daqueles anos. Aqui é o primeiro dia do “Buraco no Muro”. À direita, uma criança de oito anos. À esquerda dele, sua aluna. Ela tem seis. Ele está ensinando-a a navegar. E então, em outras partes do país, repeti isso de novo e de novo, obtendo exatamente os mesmos resultados. [“Filme Buraco no Muro- 1999”] Um menino de oito anos ensinando sua irmã mais velha. E finalmente uma garota explicando, em marati, o que é aquilo, e ela disse: “Tem um processador dentro”.

Então, comecei a publicar. Publiquei em vários lugares, anotei e quantifiquei tudo, e disse: “Em nove meses, um grupo de crianças, sozinhas com um computador, em qualquer língua, vai alcançar o mesmo nível de uma secretária de escritório no ocidente. Eu vi isso acontecer várias vezes.

Mas estava curioso para saber: o que mais eles fariam, se eram capazes de fazer tudo isso? Comecei a testar outras coisas, entre elas, por exemplo, a pronúncia. Há uma comunidade de crianças no sul da India que têm a pronúncia bem ruim em inglês, e que precisavam de boa pronúncia, pois conseguiriam melhores empregos. Dei a elas um computador com um sistema reconhecedor de fala, e disse: “Continuem falando, até ele digitar o que vocês dizem”. (Risos) Eles fizeram isso, e vejam só:

Computador: Prazer em conhecer. Criança: Prazer em conhecer.

Sugata Mitra: Terminei com o rosto dessa jovem porque supeito que muitos de vocês a conhecem.Ela agora está em uma central de atendimento em Hyderabad e deve ter torturado vocês com suas contas do cartão de crédito, (Risos) com um sotaque inglês bem claro.

Então, as pessoas disseram: “Bom, até onde isso vai? Onde vai parar?” Eu decidi que destruiria meu próprio argumento criando uma proposta absurda. Eu criei uma hipótese, uma hipótese ridícula. O tâmil é uma língua do sul da Índia, e pensei: “Será que crianças que falam tâmil numa vila do sul da Índia podem aprender a biotecnologia da replicação de DNA, em inglês, em um computador de rua?”E pensei: “Vou testá-los. Vão tirar zero. Vou passar alguns meses, vou deixá-los por alguns meses,vou voltar e eles vão tirar outro zero. Vou voltar ao laboratório e dizer que precisamos de professores”. Achei uma vila, no sul da Índia, chamada Kallikuppam. Lá, pus computadores “Buraco no muro”, baixei todo tipo de coisa na internet sobre replicação de DNA, a maioria das quais eu não entendia.

As crianças vieram correndo e disseram: “O que é tudo isso?”

Então, eu disse: “É muito específico e importante, mas está tudo em inglês”.

E elas: “Como vamos entender palavras tão grandes em inglês, diagramas e química?”

Àquela altura, eu tinha desenvolvido um novo método pedagógico e o apliquei. Eu disse: “Não faço a menor ideia. E, enfim, estou indo embora.”

Então, os deixei por alguns meses. Eles tiraram zero. Apliquei um teste com eles. Voltei depois de dois meses e eles vieram e disseram: “Nós não entendemos nada”.

Então, eu disse: “Bem, o que eu esperava?” Entã, eu disse: “Certo, mas quanto tempo vocês levaram para concluir que não entenderam nada?”

Então, disseram: “Nós não desistimos. Nós estudamos isso todos os dias”.

Então, eu disse: “O quê? Vocês não entendem e continuam olhando para a tela durante dois meses? Para quê?”

Então, uma garotinha, que vocês estão vendo agora, levantou a mão e me disse, em tâmil e inglês ruins: “Além do fato de a replicação irregular da molécula de DNA causar doenças, não entendemos mais nada”.

Então, os testei. Consegui algo impossível em termos de educação: de zero para 30%, em dois meses, no calor tropical, com um computador embaixo de uma árvore, num idioma que eles não conheciam, fazendo algo que está uma década à frente do seu tempo. Absurdo, mas eu tinha que seguir a regra vitoriana. Trinta por cento é um fracasso. “Como farei para que sejam aprovados? Eu tenho que melhorá-los em 20%.” Não consegui encontrar um professor. Só encontrei uma amiga que eles tinham, uma contadora de 22 anos de idade, que brincava com eles o tempo todo.

Então, pedi a essa moça: “Você pode ajudá-los?”

E ela disse: “De forma alguma. Não estudei ciências na escola, não tenho ideia do que eles fazem embaixo daquela árvore o dia inteiro. Não posso te ajudar”.

Eu disse: “Vou te explicar. Use o método da avó”.

Ela disse: “O que é isso?”

Eu disse: “Fique atrás deles. Quando fizerem qualquer coisa, você diz: ‘Muito bom, como você fez isso? Qual é a próxima página? Na sua idade, eu não conseguiria fazer isso’. Sabe, como as avós fazem”.

Ela fez isso por mais dois meses, e as notas subiram para 50%. Kallikuppam tinha alcançado a minha escola de referência em Nova Delhi, uma rica escola particular com um professor de biotecnologia treinado. Quando eu vi esse gráfico, vi que havia uma forma de nivelar o jogo.

Aqui está Kallikuppam.

(Crianças falando) Neurônios… comunicação.

SM: Peguei o ângulo errado da câmera, é coisa de amador, mas ela está falando, como vocês puderam perceber, sobre neurônios, com as mãos daquele jeito, dizendo que os neurônios se comunicam. Com 12 anos.

Então, como serão os empregos? Bem, nós sabemos como eles são hoje. Como será o aprendizado? Nós sabemos como ele é hoje, crianças mexendo no celular com uma mão e relutantemente indo para a escola para pegarem os livros com a outra mão.

Como será o amanhã? Será que nós não precisaremos mais ir para a escola? Será que no momento em que você precisar saber algo, em dois minutos você vai descobrir? E uma pergunta devastadora,uma pergunta que Nicholas Negroponte me fez: será que caminhamos em direção a um futuro, ou talvez já estamos nele, onde o conhecimento é obsoleto? Isso é terrível. Nós somos “homo sapiens”. O saber é o que nos distingue dos macacos. Mas veja dessa forma: a natureza levou 100 milhões de anos para fazer o macaco ficar em pé e se tornar homo sapiens. Levou apenas 10 mil anos para que o saber se tornasse obsoleto. Esta é uma grande façanha, mas devemos integrar isso ao nosso futuro.

Incentivo parece ser a chave. Se você analisar Kuppam, se analisar todos os experimentos que fiz,eles apenas diziam: “Uau”, aplaudindo o aprendizado.

Há evidências através da neurociência. A parte reptiliana do nosso cérebro, que fica no centro do cérebro, quando é ameaçada, desliga todo o resto, desliga o córtex pré-frontal, as partes que aprendem, desliga tudo isso. Punições e provas são vistos com ameaças. Nós pegamos nossas crianças, fazemos com que desliguem seus cérebros e depois dizemos: “Façam”. Por que criaram um sistema como esse? Porque precisavam disso. Houve uma época, na Era dos Impérios, em que você precisava de pessoas que podiam sobreviver sob ameça. Quando você está em uma trincheira sozinho, se você puder sobreviver, você está bem, você passou. Se não, você fracassou. Mas a Era dos Impérios se foi. O que acontece com a criatividade no nosso tempo? Precisamos reajustar esse equilíbrio, da ameça para o prazer.

Voltei para a Inglaterra em busca de avós inglesas. Eu coloquei anúncios dizendo: “Se você é uma avó inglesa e tem internet em banda larga e uma “webcam”, poderia me dar uma hora da sua semana, de graça?” Consegui 200 nas primeiras duas semanas. Conheço mais avós inglesas do que qualquer pessoa no universo. (Risos) Elas são chamadas de “a Nuvem das Avós”. A Nuvem das Avós está na Internet. Se uma criança está com problemas, direcionamos a ela uma avó. Ela entra no Skype e resolve as coisas. Eu as vi fazendo isso de uma vila chamada Diggles, no noroeste da Inglaterra, ajudando alguém numa vila de Tamil Nadu, na Índia, a 10 mil km de distância. Ela faz isso com um velho gesto: “Shhh.” Certo?

Vejam isso.

Avó: “Você não pode me pegar. Digam”. “Você não pode me pegar”.

Crianças: “Você não pode me pegar”.

Avó: “Eu sou o Homem-Biscoito”. Criança: “Eu sou o Homem-Biscoito”.

Avó: “Muito bem! Ótimo”.

Sugata Mitra: O que está acontecendo aqui? Acho que o que precisamos é analisar o aprendizado como o produto da auto-organização educacional. Se você permitir que o processo educacional se auto-organize, o aprendizado surge. Não se trata de fazer o aprendizado acontecer, mas de deixar que ele aconteça. O professor coloca o processo em movimento e então se afasta maravilhado e observa o aprendizado acontecer. Acho que é o que isso tudo está mostrando.

Mas como saberemos? Como conseguiremos saber? Bem, eu pretendo construir Ambientes de Aprendizado Auto-Organizados, AAAO. Trata-se basicamente de banda larga, colaboração e incentivo combinados. Tentei isso em várias escolas.

Isso foi testado no mundo inteiro, e professores olhavam e diziam: “Isso acontece naturalmente?”

E eu: “Sim, acontece naturalmente”. “Como você sabia disso?”

Eu dizia: “Vocês não vão acreditar nas crianças que me disseram e de onde elas são”.

Aqui está uma AAAO em ação.

SM: Isso é na Inglaterra. (Crianças falando) SM: Ele mantém a lei e a ordem, porque, lembrem-se, não há professor ao redor.

Garota: O número total de elétrons não é igual ao número total de prótons… SM: Austrália. Garota: …resultando numa carga positiva ou negativa. A carga total em um íon é igual ao número de prótons no íon, menos o número de elétrons.

SM: Uma década à frente do seu tempo.

Os AAAOs… acho que precisamos de um currículo de grandes perguntas. Vocês já ouviram isso. Sabem o que isso significa. Houve uma época em que homens e mulheres da Idade da Pedra sentavam, olhavam para o céu e diziam: “O que são essas luzes piscando?” Eles montaram o primeiro currículo, mas nós perdemos de vista essas perguntas inspiradoras. Nós o resumimos à tangente de um ângulo, mas isso não é sexy o suficiente. A forma de explicar isso a uma criança de nove anos é dizer: “Se um meteorito estivesse vindo em direção à Terra, como você saberia se ele iria ou não atingi-la?” Se ela disser: “Bem, o quê? Como?”, você diz: “Há uma coisa mágica chamada tangente de um ângulo”, e a deixe sozinha; ela vai descobrir.

Essas são algumas imagens dos AAAOs. Fiz perguntas incríveis… “Quando o mundo começou? Como ele vai acabar?”, a crianças de nove anos. Essa é sobre o que acontece com o ar que respiramos. Isso foi feito por crianças sem a ajuda de nenhum professor. O professor apenas levanta a questão, depois se afasta e admira a resposta.

Então, qual é o meu desejo? Meu desejo é que criemos o futuro do aprendizado. Não queremos ser peças de reserva para um grande computador humano, queremos? Então, precisamos projetar um futuro para o aprendizado. E tenho que… um momento… tenho que usar as palavras corretas,porque, sabe, isso é muito importante. Meu desejo é ajudar a criar um futuro para o aprendizado,ajudando crianças do mundo todo a utilizarem sua curiosidade e habilidade de trabalharem juntas.Ajudem-me a construir essa escola. Ela será chamada de “Escola na Nuvem”. Será uma escola onde crianças entram em aventuras intelectuais, guiadas por grandes questões trazidas por seus mediadores. Quero fazer isso construindo um lugar onde eu possa estudar isso. É um lugar que praticamente não tem pessoas. Há somente uma avó que cuida da saúde e segurança. O resto vem da nuvem. As luzes são ligadas e desligadas pela nuvem, etc., etc., tudo é feito pela nuvem.

Mas quero vocês para outro fim. Vocês podem criar Ambientes de Aprendizado Auto-Organizado sem casa, na escola, fora da escola, em clubes; muito fácil de fazer; Há um grande documento produzido pelo TED, que mostra como fazer isso. Se puderem, por favor, façam isso, em todos os cinco continentes, e me enviem os dados. Vou juntar tudo, passar para a Escola das Nuvens e criar o futuro do aprendizado. Esse é o meu desejo.

Só mais uma coisa. Vou levar vocês ao topo do Himalaia. A 3,7 km de altitude, onde o ar é rarefeito,construí dois computadores do “Buraco na Parede” e as crianças se amontoaram lá. E havia uma garotinha que estava me seguindo.

Eu disse a ela: “Quero dar um computador para cada um, para cada criança. Não sei, o que eu devo fazer?” E estava tentando tirar uma foto dela escondido.

De repente ela levantou a mão assim e disse: “Vá em frente”.

Acho que foi um bom conselho. Vou seguir o conselho dela. Vou parar de falar. Obrigado. Muito obrigado. Muito obrigado.

When, in 1960, still a student, I got a traveling fellowship to study housing in North America. We traveled the country. We saw public housing high-rise buildings in all major cities: New York, Philadelphia. Those who have no choice lived there. And then we traveled from suburb to suburb, and I came back thinking, we’ve got to reinvent the apartment building. There has to be another way of doing this. We can’t sustain suburbs, so let’s design a building which gives the qualities of a house to each unit.

Over a million people are killed each year in disasters. Two and a half million people will be permanently disabled or displaced, and the communities will take 20 to 30 years to recover and billions of economic losses.

If you can reduce the initial response by one day, you can reduce the overall recovery by a thousand days, or three years. See how that works? If the initial responders can get in, save lives, mitigate whatever flooding danger there is, that means the other groups can get in to restore the water, the roads, the electricity, which means then the construction people, the insurance agents, all of them can get in to rebuild the houses, which then means you can restore the economy, and maybe even make it better and more resilient to the next disaster. A major insurance company told me that if they can get a homeowner’s claim processed one day earlier, it’ll make a difference of six months in that person getting their home repaired.

And that’s why I do disaster robotics — because robots can make a disaster go away faster.

Now, you’ve already seen a couple of these. These are the UAVs. These are two types of UAVs: a rotorcraft, or hummingbird; a fixed-wing, a hawk. And they’re used extensively since 2005 –Hurricane Katrina. Let me show you how this hummingbird, this rotorcraft, works. Fantastic for structural engineers. Being able to see damage from angles you can’t get from binoculars on the ground or from a satellite image, or anything flying at a higher angle. But it’s not just structural engineers and insurance people who need this. You’ve got things like this fixed-wing, this hawk. Now, this hawk can be used for geospatial surveys. That’s where you’re pulling imagery together and getting 3D reconstruction.

We used both of these at the Oso mudslides up in Washington State, because the big problem was geospatial and hydrological understanding of the disaster — not the search and rescue. The search and rescue teams had it under control and knew what they were doing. The bigger problem was that river and mudslide might wipe them out and flood the responders. And not only was it challenging to the responders and property damage, it’s also putting at risk the future of salmon fishing along that part of Washington State. So they needed to understand what was going on. In seven hours, going from Arlington, driving from the Incident Command Post to the site, flying the UAVs, processing the data, driving back to Arlington command post — seven hours. We gave them in seven hours data that they could take only two to three days to get any other way — and at higher resolution. It’s a game changer.

And don’t just think about the UAVs. I mean, they are sexy — but remember, 80 percent of the world’s population lives by water, and that means our critical infrastructure is underwater — the parts that we can’t get to, like the bridges and things like that. And that’s why we have unmanned marine vehicles, one type of which you’ve already met, which is SARbot, a square dolphin. It goes underwater and uses sonar. Well, why are marine vehicles so important and why are they very, very important? They get overlooked. Think about the Japanese tsunami — 400 miles of coastland totally devastated, twice the amount of coastland devastated by Hurricane Katrina in the United States. You’re talking about your bridges, your pipelines, your ports — wiped out. And if you don’t have a port, you don’t have a way to get in enough relief supplies to support a population. That was a huge problem at the Haiti earthquake. So we need marine vehicles.

Now, let’s look at a viewpoint from the SARbot of what they were seeing. We were working on a fishing port. We were able to reopen that fishing port, using her sonar, in four hours. That fishing port was told it was going to be six months before they could get a manual team of divers in, and it was going to take the divers two weeks. They were going to miss the fall fishing season, which was the major economy for that part, which is kind of like their Cape Cod. UMVs, very important.

But you know, all the robots I’ve shown you have been small, and that’s because robots don’t do things that people do. They go places people can’t go. And a great example of that is Bujold. Unmanned ground vehicles are particularly small, so Bujold –

Say hello to Bujold.

Bujold was used extensively at the World Trade Center to go through Towers 1, 2 and 4. You’re climbing into the rubble, rappelling down, going deep in spaces. And just to see the World Trade Center from Bujold’s viewpoint, look at this. You’re talking about a disaster where you can’t fit a person or a dog — and it’s on fire. The only hope of getting to a survivor way in the basement, you have to go through things that are on fire. It was so hot, on one of the robots, the tracks began to melt and come off. Robots don’t replace people or dogs, or hummingbirds or hawks or dolphins. They do things new. They assist the responders, the experts, in new and innovative ways.

The biggest problem is not making the robots smaller, though. It’s not making them more heat-resistant. It’s not making more sensors. The biggest problem is the data, the informatics, because these people need to get the right data at the right time.

So wouldn’t it be great if we could have experts immediately access the robots without having to waste any time of driving to the site, so whoever’s there, use their robots over the Internet. Well, let’s think about that. Let’s think about a chemical train derailment in a rural county. What are the odds that the experts, your chemical engineer, your railroad transportation engineers, have been trained on whatever UAV that particular county happens to have? Probably, like, none. So we’re using these kinds of interfaces to allow people to use the robots without knowing what robot they’re using, or even if they’re using a robot or not. What the robots give you, what they give the experts, is data.

The problem becomes: who gets what data when? One thing to do is to ship all the information to everybody and let them sort it out. Well, the problem with that is it overwhelms the networks, and worse yet, it overwhelms the cognitive abilities of each of the people trying to get that one nugget of information they need to make the decision that’s going to make the difference. So we need to think about those kinds of challenges. So it’s the data.

Going back to the World Trade Center, we tried to solve that problem by just recording the data from Bujold only when she was deep in the rubble, because that’s what the USAR team said they wanted. What we didn’t know at the time was that the civil engineers would have loved, needed the data as we recorded the box beams, the serial numbers, the locations, as we went into the rubble. We lost valuable data. So the challenge is getting all the data and getting it to the right people.

Now, here’s another reason. We’ve learned that some buildings — things like schools, hospitals, city halls — get inspected four times by different agencies throughout the response phases. Now, we’re looking, if we can get the data from the robots to share, not only can we do things like compress that sequence of phases to shorten the response time, but now we can begin to do the response in parallel. Everybody can see the data. We can shorten it that way.

So really, “disaster robotics” is a misnomer. It’s not about the robots. It’s about the data.

So my challenge to you: the next time you hear about a disaster, look for the robots. They may be underground, they may be underwater, they may be in the sky, but they should be there. Look for the robots, because robots are coming to the rescue.

Texto em Português:

Mais de 1 milhão de pessoas morrem em desastres a cada ano. Dois milhões e meio de pessoas ficarão permanentemente inválidas ou desalojadas e as comunidades levarão de 20 a 30 anos para se recuperar e terão perdas de bilhões de dólares.

Se conseguirmos reduzir o tempo da reação inicial em um dia, podemos reduzir a recuperação geral em mil dias, ou três anos. Percebem como funciona? Se os socorristas iniciais puderem ir lá, salvar vidas, reduzir qualquer perigo iminente, isso vai ajudar outros grupos a entrarem para restabelecer a água, as estradas, a energia elétrica, ou seja, o pessoal de engenharia civil, os agentes de seguros,todos poderão entrar no circuito e reconstruir as casas, o que vai possibilitar a recuperação da economia e talvez até torná-la melhor e mais resiliente a um futuro desastre. Uma grande corretora de seguros me disse que, se conseguirem dar andamento ao pedido de um segurado um dia mais cedo, isso fará uma diferença de seis meses a menos para que a pessoa tenha sua casa reparada.

É por isso que trabalho com a robótica de desastres, porque os robôs podem fazer um desastre passar mais rápido.

Bem, vocês já viram alguns desses. São VANTs. Esses são dois tipos de VANT: uma aeronave com hélices, ou colibri; e uma com asas, um falcão. Elas são usadas extensivamente desde 2005, após o furacão Katrina. Vou mostrar como esse colibri, essa aeronave com hélices, funciona. Fantástico para engenheiros estruturais: ser capaz de ver danos em lugares que não podemos ver do chão com binóculos, ou com imagens de satélite, ou com qualquer coisa que voe a um ângulo mais alto. Mas não são apenas engenheiros estruturais e seguradoras que precisam disso. Temos coisas como essa aeronave com asas, esse falcão. Bem, ela pode ser usada em pesquisas geo-espaciais. É aí que juntamos todas as imagens e fazemos reconstruções em 3D.

Usamos ambas nos deslizamentos de Oso, no estado de Washington, porque o grande problema era a compreensão espacial e hidrológica do desastre, não a busca e resgate. As equipes de resgate tinham tudo sob controle e sabiam o que estavam fazendo. O grande problema era que o rio e o deslizamento podiam arrastar os socorristas. Não só era desafiador para os socorristas, e pelos danos às propriedades, mas também punha em risco o futuro da pesca de salmão naquela região do estado de Washington. Eles precisavam entender o que estava acontecendo. Em sete horas, partindo de Arlington, dirigindo do Posto de Comando de Incidente até o local, pondo os VANTs para voar, processando os dados, voltando ao posto de comando em Arlington… sete horas. Em sete horas, demos a eles dados que poderiam ter somente em dois ou três dias de qualquer outra maneira — e com uma maior resolução. Um divisor de águas.

Não pensem apenas nos VANTs. Digo, eles são sexy, mas lembrem-se: oitenta por cento da população mundial vive próximo à água, e isso significa que nossa infra estrutura crítica — os locais aonde não podemos chegar, como pontes e coisas assim. É por isso que temos veículos marítimos remotos, um dos quais vocês já conheceram, que é o SARbot, um golfinho quadrado. Ele fica submerso e utiliza sonar. Bem, por que veículos marítimos são tão importantes e por que são muito, muito importantes? Eles passam despercebidos. Pensem no tsunami no Japão… 644 km de área costeira totalmente devastada, duas vezes mais devastação costeira do que a causada pelo Katrina, nos EUA. Estamos falando de pontes, dutos, portos… devastados. E se você não tem portos, não terá por onde receber suprimentos suficientes para manter a população. Isso foi um grande problema no terremoto no Haiti. Por isso, precisamos de veículos marítimos.

Bem, vejamos o que SARbot via. Estávamos trabalhando num porto de pesca. Conseguimos reabrir o porto em quatro horas, usando o sonar. Disseram que levaria seis meses até que conseguissem uma equipe de mergulhadores e que eles levariam duas semanas. Eles perderiam a temporada de pesca do outono, a de maior importância para a economia do local, que é parecida com Cape Cod.VMNTs, muito importantes.

Mas sabem, todos os robôs que mostrei são pequenos, isso porque eles não fazem o que os humanos fazem. Eles vão a lugares onde pessoas não podem ir. Um grande exemplo disso é Bujold.Veículos terrestres não tripulados são especialmente pequenos, então Bujold…

Bujold foi usada amplamente no World Trade Center, para verificar as torres n° 1, 2 e 3. Ela sobe pelos destroços, desce por eles, vai a locais profundos. Só para se ter ideia da visão que Bujold teve do World Trade Center, vejam isto. Trata-se de um desastre aonde não é possível enviar uma pessoa ou um cão, e o local está em chamas! A única chance de alcançar um sobrevivente na fundação do prédio é passando pelo meio das chamas. O calor era tanto que derreteu as esteiras de um dos robôs; começaram a se soltar. Os robôs não substituem pessoas, nem cães; nem colibris, nem falcões, nem golfinhos. Eles fazem coisas novas. Eles auxiliam os socorristas, os especialistas, de formas inovadoras.

O maior problema não é tornar os robôs menores. Não é torná-los mais resistentes ao calor. Não é criar mais sensores. O maior problema são os dados, a informática, porque essas pessoas precisam obter os dados certos, na hora certa.

Não seria ótimo se os especialistas pudessem ter acesso imediato aos robôs, sem ter que perder tempo dirigindo até o local do desastre, tendo quem quer que fosse o controle dos robôs via internet? Bem, vamos pensar nisso: um trem com substâncias químicas, descarrilando numa área rural. Quais as chances de especialistas, engenheiros químicos, engenheiros de transporte ferroviário, terem sido treinados em qualquer VANT que essa região possa ter? Tipo, provavelmente zero. Por isso, estamos usando esses tipos de interface para permitir que as pessoas usem os robôs sem saber que robô estão usando, nem mesmo se estão ou não usando um robô. O que os robôs fornecem a nós e aos especialistas são dados.

O problema então é: quem recebe quais dados, e quando? Uma coisa possível é enviar toda a informação a todos e deixá-los pesquisá-la. Bem, o problema é que isso sobrecarrega as redes e, pior ainda, sobrecarrega as habilidades cognitivas de todas as pessoas que tentam receber aquele pedacinho de informação de que precisam para tomar a decisão que fará a diferença. Então, precisamos pensar sobre esses tipos de desafio. Então, são os dados.

Voltando ao World Trade Center, tentamos resolver esse problema simplesmente gravando os dados da Bujold só quando ela estava bem fundo nos destroços, porque é isso que a equipe de busca e resgate urbana disse que queria. O que não sabíamos na época era que os engenheiros civis teriam adorado, precisado dos dados conforme gravávamos as colunas de vigas, os números de série, os locais, conforme entrávamos nos destroços. Perdemos dados valiosos. Então, o desafio é obter todos os dados e levá-los às pessoas certas.

Bem, eis outro motivo. Aprendemos que alguns edifícios, como escolas, hospitais, prefeituras, são inspecionados quatro vezes por agências diferentes, em todas as fases desocorro. Agora estamos vendo que ao pegar os dados dos robôs e compartilhá-los, não só podemos fazer coisas como comprimir essa sequência de fases, para reduzir o tempo de reação, mas podemos começar a reagir simultaneamente. Todos podem ver os dados. Podemos encurtar o tempo assim.

Na verdade, “robótica de desastres” é um termo impróprio. Não se trata dos robôs. Trata-se dos dados.

Então, meu desafio a vocês é: na próxima vez em que ouvirem falar de um desastre, procurem pelos robôs. Eles podem estar sob o solo, podem estar sob a água, podem estar no céu, mas precisam estar lá. Procurem pelos robôs, porque eles estão indo ao seu socorro.

When, in 1960, still a student, I got a traveling fellowship to study housing in North America. We traveled the country. We saw public housing high-rise buildings in all major cities: New York, Philadelphia. Those who have no choice lived there. And then we traveled from suburb to suburb, and I came back thinking, we’ve got to reinvent the apartment building. There has to be another way of doing this. We can’t sustain suburbs, so let’s design a building which gives the qualities of a house to each unit.

Habitat would be all about gardens, contact with nature, streets instead of corridors. We prefabricated it so we would achieve economy, and there it is almost 50 years later. It’s a very desirable place to live in. It’s now a heritage building, but it did not proliferate.

In 1973, I made my first trip to China. It was the Cultural Revolution. We traveled the country, met with architects and planners. This is Beijing then, not a single high rise building in Beijing or Shanghai. Shenzhen didn’t even exist as a city. There were hardly any cars. Thirty years later, this is Beijing today. This is Hong Kong. If you’re wealthy, you live there, if you’re poor, you live there, but high density it is, and it’s not just Asia. São Paulo, you can travel in a helicopter 45 minutes seeing those high-rise buildings consume the 19th-century low-rise environment. And with it, comes congestion, and we lose mobility, and so on and so forth.

So a few years ago, we decided to go back and rethink Habitat. Could we make it more affordable? Could we actually achieve this quality of life in the densities that are prevailing today? And we realized, it’s basically about light, it’s about sun, it’s about nature, it’s about fractalization. Can we open up the surface of the building so that it has more contact with the exterior?

We came up with a number of models: economy models, cheaper to build and more compact; membranes of housing where people could design their own house and create their own gardens. And then we decided to take New York as a test case, and we looked at Lower Manhattan. And we mapped all the building area in Manhattan. On the left is Manhattan today: blue for housing, red for office buildings, retail. On the right, we reconfigured it: the office buildings form the base, and then rising 75 stories above, are apartments. There’s a street in the air on the 25th level, a community street. It’s permeable. There are gardens and open spaces for the community, almost every unit with its own private garden, and community space all around. And most important, permeable, open. It does not form a wall or an obstruction in the city, and light permeates everywhere.

And in the last two or three years, we’ve actually been, for the first time, realizing the quality of life of Habitat in real-life projects across Asia. This in Qinhuangdao in China: middle-income housing, where there is a bylaw that every apartment must receive three hours of sunlight. That’s measured in the winter solstice. And under construction in Singapore, again middle-income housing, gardens, community streets and parks and so on and so forth. And Colombo.

And I want to touch on one more issue, which is the design of the public realm. A hundred years after we’ve begun building with tall buildings, we are yet to understand how the tall high-rise building becomes a building block in making a city, in creating the public realm. In Singapore, we had an opportunity: 10 million square feet, extremely high density. Taking the concept of outdoor and indoor, promenades and parks integrated with intense urban life. So they are outdoor spaces and indoor spaces, and you move from one to the other, and there is contact with nature, and most relevantly, at every level of the structure, public gardens and open space: on the roof of the podium, climbing up the towers, and finally on the roof, the sky park, two and a half acres, jogging paths, restaurants, and the world’s longest swimming pool. And that’s all I can tell you in five minutes.

Texto em Português:

Em 1960, ainda estudante, eu ganhei uma bolsa de estudos para estudar moradias na América do Norte. Viajamos pelo país. Vimos arranha-céus de moradia pública em todas as principais cidades: Nova Iorque, Filadélfia. Quem não tinha escolha morava lá. E viajamos de subúrbio em subúrbio, e eu voltei pensando: “Temos que reinventar os prédios de apartamentos. Há de haver outro modo de fazer isso. Não podemos manter subúrbios, então vamos desenhar um prédio que dê as qualidades de uma casa a cada unidade.”

O Habitat teria foco em jardins, contato com a natureza, ruas, em vez de corredores. Nós pré-fabricamos para fazermos economia, e aí está, quase 50 anos depois. É um lugar bastante desejável para morar. Agora é um edifício histórico, mas não se proliferou.

Em 1973, fiz minha primeira viagem à China. Era a Revolução Cultural. Viajamos pelo país, e nos reunimos com arquitetos e urbanistas. Esta é Pequim naquela época, nem um único arranha-céu em Pequim ou Xangai. Shenzhen nem existia como cidade. Quase não havia carros. Trinta anos mais tarde, esta é Pequim hoje. Esta é Hong Kong. Se você é rico, mora aqui, se é pobre, mora aí, mas a densidade é alta, e não só na Ásia. Em São Paulo, você pode voar de helicóptero por 45 minutos vendo arranha-céus consumindo o ambiente de poucos pisos do século 19. E com isso vem o congestionamento, perdemos mobilidade, e assim por diante.

Então há poucos anos decidimos voltar e repensar o Habitat. Poderíamos torná-lo mais acessível?Poderíamos realmente alcançar essa qualidade de vida nas densidades predominantes hoje em dia?E percebemos que trata-se basicamente da luz. Tem a ver com o sol, com a natureza, tem a ver com a fractalização. Podemos abrir a superfície do prédio para que ele tenha mais contato com o exterior?

Criamos diversos modelos: modelos econômicos, mais baratos de construir e mais compactos;membranas habitacionais onde as pessoas pudessem desenhar a própria casa e criar os próprios jardins. Então decidimos tomar Nova York como caso de teste, e analisamos parte baixa de Manhattan. Mapeamos toda a área construída de Manhattan. À esquerda, está Manhattan hoje: azul para habitações, vermelho para prédios comerciais, varejo. À direita, nós a reconfiguramos: os prédios comerciais formam a base, e os 75 andares acima são apartamentos. Há uma rua suspensa no 25º andar, uma rua comunitária. Ela é permeável. Há jardins e espaços abertos para a comunidade, quase todas as unidades com seu próprio jardim particular, e espaço comunitário por toda parte. E o mais importante, permeável, aberto. Não forma um muro ou obstrução na cidade, e a luz permeia todos os lugares.

E nos últimos dois ou três anos, pudemos realmente, pela primeira vez, perceber a qualidade de vida do Habitat em projetos de vida real por toda a Ásia. Isto é em Qinhuangdao na China: habitações para renda média, onde há uma norma de que todo apartamento deve receber três horas de luz do sol. A medição é feita no solstício de inverno. E sendo construído em Cingapura, novamente habitações de renda média, jardins, ruas comunitárias, parques, etc. E Colombo.

Quero tocar numa outra questão, que é o design da esfera pública. Cem anos após começarmos a construir com prédios altos, ainda precisamos compreender como o arranha-céu se torna um bloco de construção da cidade, na criação da esfera pública. Em Cingapura, tivemos uma oportunidade: 10 milhões de metros quadrados, densidade extremamente alta, tomando o conceito de ambientes externos e internos, passeios e parques integrados com intensa vida urbana. Logo temos espaços externos e internos, e você passa de um para o outro, e há contato com a natureza, e, principalmente, em cada nível da estrutura, jardins públicos e espaço aberto. No telhado do pódio,subindo pelas torres, e finalmente no telhado, o parque do céu, dois acres e meio, pistas para correr, restaurantes, e a piscina mais longa do mundo. E isso é tudo que eu posso contar a vocês em cinco minutos.